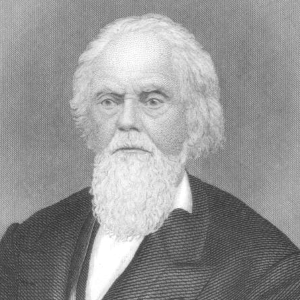

[[Luther Lee preached this sermon on Prohibitory Laws in 1841. Two years later (1843) the Wesleyan Methodist Connection (now Wesleyan Church) was founded and Luther Lee was elected its president (1844).]]

Romans [13:3] For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil.

In this chapter, the apostle, as we understand him, vindicates the rightful existence of civil government, and lays down certain general principles respecting its design, its powers and its limitations. In the text which we have before us for contemplation this evening, we learn the object to which civil government should be directed, viz., to the suppression of vice, and the support of virtue. The apostle, in this text, most obviously speaks of rulers in view of what they should be, and not in view of what they too frequently are. It was the design of God, in ordaining the existence of civil government, that rulers by whom it is administered, should be a terror to evil doers, and support to the virtuous, and a protection to them that do well; hence, of the same rulers who are said to be a terror to the evil, it is said in the fourth verse, with reference to them that do well, “he is the minister of God unto them for good.” [Romans 13:4] From this it will be seen that in all those cases, where government has been directed to purposes of oppression, to the injury of any portion of the governed, or to the suppression of virtue, or in which it has been made to yield any support to vice, there has been a departure from the design of the institution, and a violation, not only of the rights and interests of man, but of the law of God.

We might point out various instances in which government has been perverted, and instead of being a terror to evil doers, it has thrown its protecting arm around the workers of iniquity, and has become a terror to them that do well, but we must confine our remarks upon this subject to one point, viz., the countenance which government has given to intemperance. The subject assigned to me in the order of the series of temperance sermons which is now nearly finished, is that of “prohibitory laws.” This subject I deem of the first importance, and though I cannot help feeling a regret that it had not been entrusted to more able hands, and especially to hands that might have sent to out to the public with a stronger personal influence, echoing with a name that would sound more grateful upon the public ear, yet as it has been committed to me, I shall discharge the obligation imposed upon me to the best of my ability, by attempting to prove that government, “instead of licensing the sale of intoxicating drinks, ought to prohibit the sale of the same under severe penalties.”

In order to establish the above position, I shall attempt to show—

I. That a prohibitory law is necessary to consummate the temperance reformation;

II. That the passage of such a law comes perfectly within the design and powers of civil government; and,

III. That civil government is bound by the strongest moral obligation, to enact and enforce such a law.

I. It is necessary to resort to prohibitory law to consummate the temperance reformation.

1. To license the sale of intoxicating drinks tends to produce intemperance, as every reflecting mind must see. We shall not in this place attempt to prove that moderate drinking is injurious, as we might do, but only that it leads to [intemperate] drinking. So long as the habit of drinking is continued, the habit of drunkenness cannot be broken up. This is a point so well established, that it is unnecessary to waste time to prove it again. If there were no moderate drinkers, there would soon be no drunkards; hence, the success of the temperance cause depends upon our success in persuading men to wholly abandon the use of intoxicating drinks. The question then is this, and it is a plain one, Does the act of licensing men to sell the evil spirit to be drunk, help or hinder us in the work of persuading our neighbors not to drink it? It cannot be denied that the act of licensing the sale of intoxicating drink is a decided and public testimony in favor of drinking it, and every man who in any way aids in giving licenses, and all who approve of the license system, declare to the world their acts and principles, that it is right to drink intoxicating liquor, and that it ought to be drunk. If it be right to license a man to sell spirit, it must follow that it is right for such person to sell it; and if it be right for one man to sell spirit to be drunk, it must also follow that it is right for others to buy and drink spirit, for no man can have a right to sell to be drunk, what another has not a right to buy and drink.

The above view shows that the present system of granting licenses to men to sell intoxicating drinks, is worse than to have no law on the subject, so far as moral influence is concerned. If there was no law, there would be no testimony on the subject, but the license law is a testimony speaking in the voice of the State, declaring through her statute books, that in the opinion of the people of this Commonwealth, intoxicating liquors ought to be sold and drunk.

But the present license system not only exerts the influence of moral suasion in favor of the use of intoxicating drinks, but it has the effect of a protective law. The law professedly grants licenses for the public good, hence it presumes that it is necessary that there should be some portion of our citizens engaged in the business of selling intoxicating drinks; and to secure this object, the law prohibits all but a certain number of licensed individuals to sell, to encourage them in it by making it profitable. The law does not restrict the quantity to be sold, but the number of persons by whom it is to be sold. If then, a man can make it profitable to sell spirit in a community where every one has the right of selling, he can make it much more profitable where the business is restricted by law to a very few individuals in each town. It is clear from these views, that the present license law tends to protect and encourage the sale of intoxicating drinks, and must therefore promote intemperance.

2. Moral suasion, without the aid of prohibitory law, is not sufficient to restrain all men from vice. There are various reasons why it is so—two of the principal of which we will notice.

First, All men are not sufficiently enlightened to see and feel the force of moral principle, and, therefore, cannot be controlled by moral suasion.

Secondly, All men are not honest, and therefore disregard the voice of moral principle, and resist the influence of moral suasion. Taking the world as we find it, these two considerations show, most clearly, the necessity of prohibitory law to restrain men from vice. But it is often objected to this view, that nothing is gained, in a moral point of light, by restraining men from vice by the force of law, inasmuch as it does not reform the disposition of the heart. To this it may be replied, that three important advantages may be gained by prohibitory law, admitting that it has no direct tendency to make the heart better.

First, it may prevent the formation of inveterate habits of vice, and the individual be thus kept within the influence of moral suasion.

Secondly, it will prevent all the individual and personal evils which would follow the commission of crimes thus restrained by law.

Thirdly, the influence of the bad example is prevented, when men are restrained from vice by the force of law.

I trust I have now shown, first, that the sale of intoxicating drink is a public evil, and second, that moral suasion will not restrain it; we are, therefore, left to choose between resorting to law on this subject, or abandoning law on all other subjects. In no other way can we avoid the most glaring inconsistency.

Why not suppress horse-stealing [[Ex. 22:1]] by moral suasion, as well as to suppress rum-selling by the same process. It must appear easier to suppress horse stealing by the force of public opinion, than rum-selling. Horse-stealing cannot look back to the time when it could plead the sanction of law, but rum-selling will always be able to do this. Horse-stealing cannot name the time when it was reputable with the community generally, when the different churches had horse-stealing members and deacons and ministers, but rumselling will always be able to do this. No one can hope to make rum-selling more disreputable than horse-stealing, and yet moral suasion is not sufficient to suppress horse-stealing without the aid of law; yea, moral suasion and law combined cannot wholly suppress it; how vain then, to think of suppressing rum-selling without law.

Why not suppress false-swearing, slander, profane swearing, and Sabbath-breaking, by moral suasion without law? Why punish the crime by law, and at the same time legalise the cause that produces the crime? Drunkenness is prohibited by law in this Commonwealth; why not then prohibit the sale of intoxicating drinks, which certainly leads to the crime of drunkenness? Moral suasion can never be arrayed against rum-selling with a more united and powerful influence than it has been against the other vices above named; the civil law has proclaimed its penalty from our seats of justice; every pulpit in the land has thundered and lightened with the law of God against stealing, lying, profane swearing, &c, and yet these evils have not been put down; [[Drinking/drunkenness: Lev. 10:8-11; Deut. 21:18-21; Matt. 24:48-51; Luke 12:45-48; 1 Cor. 5:11-13.

False-swearing: Lev. 6:1-7; Deut. 19:18-19; Matt. 5:33-37; Acts 5:1-11.

Slander/evil-speaking: Deut. 22:18-19; 2 Cor. 12:20-13:2; 1 Pet. 2:1.

Profane-swearing: Lev. 19:12; 24:10-16.

Sabbath-breaking: Ex. 35:1-3; Num. 15:32-36; Neh. 13:21; Jer. 17:27; Acts 20:7; 1 Cor. 16:2.]] it must therefore be a hopeless case to think of preventing the sale of intoxicating drinks by moral suasion, in view of the strong hold which it has upon the community, the many advocates it finds, and the countenance of the civil law. In conclusion, the experience of the world proves that moral suasion will not restrain all men from vice. It failed to do it amid the hallowed bowers of Eden; it failed to do it on the day when the earth received the blood of righteous Abel, at the hand of the first murderer [[Gen. 4:10-12; 9:6]]; it was not sufficient in the days of Noah’s ministry [[Gen. 6:11-13; Matt. 24:37-39; Luke 17:26-27; 2 Pet. 2:5]]; while the waters were gathering to drown the old world; it failed on the day when Abraham prayed for devoted Sodom [[Gen. 18:20-33; Luke 17:28-30; 2 Pet. 2:6; Jude 1:7]], as the clouds of God’s wrath were gathering, surcharged with fire; it was not sufficient at Sinai’s base, while God rested in a cloud upon the summit, blazing with lightning [[Exodus 19:16-20; 20:18-21]] and uttering his command in the thunder’s voice, “Thou shalt do no sin;” moral suasion was not equal to the reformation of all men, under the unearthly and soul-subduing eloquence of the Son of God. If then prohibitory law is necessary to complete the temperance reformation, we will attempt to show;

II. That such a law comes within the design and power of civil government. By a prohibitory law I mean a law prohibiting the sale of intoxicating drinks, to be used as such. That government has such right and power must appear from the following considerations.

1. There is no valid reason in law, equity or morals, why government may not enact such a law. If it be said that such a law would be unconstitutional, the reply is two-fold;

First, It is demanded what part of the constitution would be violated by such a law? This has never been shown. Let those who talk about the constitution, give the chapter and verse on which they found their objection, and they shall receive attention.

Secondly, If it were a fact that such a law would be unconstitutional, the reply is, let the constitution be altered so as to remove this objection out of the way. The constitution makes provision for its amendment, and hence, if, as the objection supposes, the obstacles in the way of a [prohibitory] law, is found in the constitution, nothing can be plainer than that government has power to remove that obstacle out of the way, and hence, government must have power to pass the law in question.

Is it objected that such a law would be a violation of personal rights? It is demanded what rights would be violated by such a law? No right but the right to sell rum! And pray what right has any man to sell rum? No man would have a legal right to sell rum, when the law should forbid it; no legal right would therefore be violated by a prohibitory law. And no man ever had a moral right to sell rum, nor is it possible that such a moral right exist, therefore no moral right would be violated by such a law. Now as all rights are such by law or morals, it follows that no right would be violated by a law that should prohibit the sale of rum.

2. Laws already exist which involve the principle that would be involved in a law that should prohibit the sale of intoxicating drinks. The present license law involves, to all intents and purposes, the right to pass a prohibitory law. Though I have said it is its operation essentially a protective law, yet it protects in a manner which involves the right to prohibit. The license law protects a few persons by ordaining that no others shall sell intoxicating drinks. Government then exercises the right of prohibiting ninety-nine out of a hundred of all the people the business of selling rum; and if they have this right, they must have the right of prohibiting one more on each hundred which would be the very thing for which I contend. But what must settle this question beyond dispute, is the fact that the few that are permitted to sell intoxicating drinks, are dependant for their right so to do upon government. They must buy the right to sell rum, of government, and pay their money for it. This every man does who takes a license. Now as government sells the right to vend intoxicating drinks, it shows that the right of vending is in the hands of government, and not in the hands of the people individually; otherwise government sells what is not its own. If then the right to vend intoxicating drinks belongs to the government, to grant or withhold, it follows conclusively that government has power to pass a prohibitory law. The very fact that no man has a right to sell without obtaining license from government, proves that government has the right to prohibit the sale thereof.

There are other laws which involve the same principle Such as the law regulating poison, the law prohibiting the sale of damaged meat, the law respecting exhibitions, theatres, &c., of which I will not speak in detail. The laws all involve the same principle that would be involved in a law prohibiting the sale of intoxicating drinks, and if it be decided that government has not the power to pass such a law, such decision must sweep all these other laws by the board.

3. To deny that government has power to pass such a law as that for which we contend, would be to subvert civil government, by removing from its reach every object which it is designed to secure. What is the design of government? or by what rules are we to determine the rights and powers of government? When these questions are answered, it must appear plain, that if government cannot rightfully enact the law in question, all enactments must be nullity, and government can hold no rightful existence.

By what rule then, are we to determine what government may do, and what it may not do? If we infer the power of government from the general design of the institution, it must follow that the right and power is equal to the accomplishment of the design. What, then, is the design of government from which we are to infer its rights and powers?

Is it to suppress vice and immorality? Then must government have power to suppress vice and immorality, and that involves the right to suppress rum-selling, which is the cause of more vice than all other causes put together.

Is it the design of government to suppress crime? [Is it] clear that there can be more effectual measures to accomplish this design, than to suppress the sale of intoxicating drinks?

Is government designed to protect the weak against the strong? No class [needs] that protection more than the drunkard, his abused wife, and hungry and half-naked children—they need the strong arm of the law to protect them against the ravages of the rum-seller.

Is government designed to render men secure in their persons and property? It is known to all that neither are nor can be secure where men are allowed to vend and drink alcohol without restraint.

Is government designed to promote the general welfare? No one can deny that the suppression of sale of intoxicating drinks would do more to promote such general welfare than any other one measure government could adopt. It is clear, then, that if the rights and powers of government are to be inferred from the general design of the institution, government must have power to suppress the sale of intoxicating drinks.

But it may be said that the rights and powers of government are to be inferred from the individual rights of the people. Those who take this ground, must admit that government has a right to do just what the people would have a right to do, were they assembled en masse to make rules for themselves. Now, nothing can be more plain than that it is the individual right of every person to refuse to sell, buy or drink rum; and if the right of government is inferred from the rights of the people, government must have the right, standing in the place of each and all the people, to determine for them that they shall neither vend nor drink rum. To deny this would be to deny that the rights of government may be inferred from the individual rights of the people.

Do we infer the powers of government from the principles of righteousness as taught in the Bible?—then must government have power to carry out and enforce those principles. And when we look into this book of books, we find that it forbids all drunkenness, and all incentives to drunkenness, and all selling or giving away of intoxicating drink. Hab. [2:15]: “Wo unto him that giveth his neighbor drink, that putteth his bottle to him.” If then the Bible is to be the standard, it will sweep this unholy traffic from the land and the world. If government has not power to pass such a prohibitory law on this subject, it must be incapable of passing such laws on other subjects, and government itself must become a nullity. With these considerations I will leave this part of the subject, trusting that I have shown to the satisfaction of the candid that it comes perfectly within the scope and power of civil government to prohibit by law the sale of everything which is hurtful to the community, including intoxicating drinks among the evils to be prohibited.

III. We are to show that government is bound by the highest moral obligation to enact and enforce a prohibitory law in relation to the sale of intoxicating drinks.

1. The simple right of government involves the obligation to do it. To make out a moral obligation to perform any act, two things must be proved.

First, It must be shown that the proposed act is right in itself, and that it ought to be done. This is most obviously the case in relation to the subject in question. Nothing can be more plain, than that the vending of intoxicating drinks ought to be stopped. The whole preceding argument goes to show this.

Secondly, To make out a moral obligation, it must be shown that the person or party appealed to is authorized to perform such acts.

Suppose it to be right to hang a man for murder, it will not follow that we have a right to hang the murderer wherever we can find him, for we are not authorized to perform the work of hanging. Now in the case before us, government is the party authorized to perform the act, and therefore, upon government must the obligation rest.

The argument stands thus:

The sale of intoxicating drinks ought to be prevented;

But government alone has power to prevent it;

Therefore, government must be morally bound to prevent the sale of intoxicating drinks.

2. The design of God, in the establishment of civil authorities, proves the point in question. My text says, “Rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same: For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain; for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.” [Rom. 13:3-4]

This most clearly shows, that the design of the establishment of rulers is, to protect and support virtue, and to punish and suppress vice, and the obligation to suppress vice most clearly involves the obligation to suppress the sale of intoxicating drinks. To put it in the form of a regular argument, I say,

It is the duty of government to suppress vice;

The vending of intoxicating drinks is the source of more vice than any other one cause;

Therefore, it is the duty of government to suppress the vending of intoxicating drinks.

3. The individual responsibility of those who administer government, involves the duty in question.

Every man is bound to do all that he can, that is right and lawful, to suppress intemperance, and when a man is clothed with [governmental] power, it only enlarges his power to do, without diminishing his obligation to do; he is still as much bound to do all he can as he was while a private citizen, possessing an enlarged capacity to do. Let us illustrate this point:

I am honored this evening with the presence of Dr. Huntington, who is the President of the Temperance Society, at whose call I deliver this address. As a member of the Temperance Society, Dr. Huntington is pledged to do all he can to suppress intemperance, and to discountenance the sale and use of intoxicating drinks. But I am informed that the Dr. sustains another important relation to this community: he is the Mayor of your city, and as such is charged to a certain extent, with the administration of law.* [* Dr. Huntington, who was at the time both President of the Temperance Society, and Mayor of the city, was in the chair, while the Sermon was delivered. This gave a point to argument at the moment, which can hardly be felt at a distance of time and place.] He holds in his hand especially, what is called the license law. As a temperance man, we have seen that he is bound to do all he can to discourage the use of intoxicating drinks, and this pledge to do all he can, consistently with law and religion, to discountenance the use of intoxicating drinks, covers every relation in which he is called to act, and binds him equally when he acts as the administrator of the license law, when he acts as a physician, and when he acts as a private citizen: he, therefore, can no more give official sanction to the sale and use of intoxicating drinks without violating his temperance pledge, than he could give private sanction to the same operation. It would be one of the greatest absurdities to suppose that he is bound, as citizen Huntington, to do all he can to suppress the sale and use of intoxicating drinks, and that he is at liberty, at the same time, as Mayor Huntington, to wield the arm of the law in protection of the sale and use of intoxicating drinks! These remarks have been made to illustrate the principle that men’s temperance obligations bind them in every relation, and hence, what we have said of a particular case, is true of every man clothed with governmental powers. When men are elected to make laws for the people, they are not released from their individual obligations. A man bound to do all he can at home in his individual capacity to suppress intemperance, is no less bound to do all he can when in the legislative hall. Men are not all called to act in the same sphere, and hence, when it is said that men are bound to do what they can for the suppression of intemperance, it is implied that it relates to the sphere in which each is called to act. It is a broad principle, which no man can deny, that every man is bound to do all that he can to suppress intemperance. Now, if I am bound to do all I can as a minister, because that is the sphere in which I act, and another is bound to do all he can as a physician, because that is his sphere of action, then it must follow that a legislator is bound to do all he can in law making, because that is the sphere in which he acts; it is therefore plain that government is under a moral obligation to suppress the sale of intoxicating drinks by law.

There is another way in which the moral obligation of government may be proved from the individual obligations of the people. Government is bound to do just what the people would be bound to do, were they assembled en masse to make their own laws. If then the sale of intoxicating drinks ought to be suppressed, it follows that the people would be bound to suppress it, were they assembled to make rules for the government of the whole; therefore, as the government is bound to carry out the obligations of the people, government must be bound to suppress the sale of intoxicating drinks.

It may be well here to correct a common mistake, which is this: many seem to suppose that government is bound to carry out the will of a majority of the people. This is not true, especially when we speak of moral obligation. Government is bound to do what the people would do, were they assembled en masse, but government is under obligation to do what the people would be bound to do, were they assembled. Legislatures are not bound by the will of a majority of their constituents, but by the law of right. They cannot be bound by the will of the people, when that will is morally wrong. The people can have no right to entertain or express a will that is morally wrong; and surely, government cannot be bound by a will which the people have no right to entertain or express. Indeed, legislators themselves become transgressors, when they obey the wrong will of their constituents. Suppose the whole people join in requiring their representatives to pass and give their official sanction to a law that is morally wrong, has government a right to comply with the requisition? No more than an individual, or a number of individuals have a right to commit sin for hire.

Government is not only not bound by the wrong will of the people, but it is bound by the allegiance due to the throne of God, to resist every such wrong will, even at the sacrifice of life. Better aspire to a martyr’s crown, than to set their seal to a law that is morally wrong, though the whole array of fallen spirits in this world should rise up to require it at their hands.

We will now close this argument by stating it thus:

Every person is bound to do all that is right to suppress intemperance;

It is right for those who are clothed with [governmental] powers to suppress intemperance by a prohibitory law;

Therefore, government must be bound to enact and enforce a prohibitory law for the suppression of intemperance.

4. The express declarations of God’s Word involve the obligation in question. We will not enlarge upon this argument, but will only quote one text as a specimen of a many of a similar character which might be adduced.

Jer. [21:12] “O house of David, thus saith the Lord, Execute judgment in the morning, and deliver him that is spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor, lest my fury go out like fire, and burn that none can quench it, because of the evil of your doings.”

There are two points in relation to this text worthy of particular attention, viz. the persons addressed and the work they are required to do. The text was addressed to the house of David, which was, in other words, the government of the nation. So far, therefore, as the text has an application now, it is applicable to civil government; nor does it alter the nature of the obligation, whether the power to govern be in the hands of a king, a president, or an elective legislature, or in a government of a mixed character. What then, is the work which this text requires government to do? It is to “execute judgment and deliver the spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor.” Who, then, is spoiled but the drunkard, who are the oppressed and ruined but the outraged wife and worse than fatherless children? And who is the oppressor but the rum-seller? And how can government deliver the spoiled out of the hand of this oppressor in any way so proper and effectual, as to pass a prohibitory law, which shall put a stop to his unholy and ruinous business?

I trust I have now shown first, that a prohibitory law is necessary to complete the temperance reformation; secondly, that government has all necessary authority to pass such a law, and thirdly, that government is held responsible for the passage and enforcement of such a law, by the highest moral obligation; and having, as I believe, established these points, I will close my remarks by drawing a few [inferences] from the premises.

1. An awful responsibility rests upon this nation, and upon the individual States of this nation. Instead of suppressing this great evil, government has employed its influence and power to protect it. We import by law, we manufacture, and we licence the cause of all sorts of crime, misery and death. Now, when we consider that this whole business is legislation against God, and by a nation too, with their Bibles in their hands, what a cloud of guilt must rest upon the nation, and what a storm of righteous yet fearful retribution must be gathering in the chambers where Jehovah treasures up his wrath and his thunder against the day of vengeance? So long as government tolerates the traffic in intoxicating drink, so long must the nation, and each State, pursuing the same policy, be responsible for the fearful consequences which flow from it, and the amount of guilt can be measured only by the number and enormity of the crimes, and the weight of wo produced. Intellects enough have been blighted and turned into night to have eclipsed any other age but this, and wrapped the world in darkness. Nerves and muscles enough have been enervated to have rendered puerile and helpless any other age but this one of wonderful enterprise and inventions. Property enough has been wasted to have banished hunger from the world, and to have supplied garments for all the naked and destitute of the human race.

Consider the tears that have been shed, the sighs that have been uttered, the groans that have responded to groans, the hearts that have been broken, and the spirits that have been ruined; consider no more than woman’s misery and orphan’s tears, and how fearful must be the responsibility?

2. This responsibility, under our free system of government, rolls back upon the people, and they have got to bear it in their individual capacity. The people have it in their power to correct these evils, to repeal every law which gives any countenance to the deadly traffic, and to enact and sustain other laws, such as the crime demands; laws that should impose a withering penalty upon the business of poisoning men with alcohol. If then the people have it in their power to correct these evils, upon them must the responsibility rest.

But I am aware that men are not apt to feel, as individuals, the responsibility that belongs to the whole. Feel it or not feel it, it is theirs, and they will find it out in the day of retribution, if not before. That responsibility which rests upon the whole, rests upon each, for the responsibility of the whole is made up of the responsibility of each individual, therefore, each individual must bear this fearful amount of responsibility upon his own shoulders. Suppose the lawful punishment of a crime to be ten years’ imprisonment; suppose that crime to be committed by ten persons jointly, where does the responsibility and guilt lie? How will you punish the offence? Will you imprison one of them ten years to satisfy the law, and let the other nine escape? Or will you inflict one-tenth part of the punishment upon each, keeping each in prison one year, making up the ten years required by law between them? or will you imprison each and all of them for the whole offence, making each responsible for the whole crime? I answer, you will do the latter. The fact that many combined together to commit a crime does not lessen the responsibility and guilt of each. So with the consequences of rum-selling. The whole people who countenance the traffic are responsible for all its consequences, and this responsibility falls with all its weight upon each individual of the whole as though he had to bear it alone. How fearful then is the responsibility of those, who lend their influence in any way to sustain a practice so fraught with crime, misery, anguish and death?

3. How fearful is the responsibility of the vender of intoxicating drinks? The vender is no less guilty than he would be if there were no law in his favor. The license law confers no moral right; the law itself is morally wrong, and that which is morally wrong cannot form the basis of moral right. Civil law does not make any thing morally right—it is not the design of law to create right, but to secure what is previously right, and right is not founded upon law, but law should be founded upon right. The vender, therefore, is just as guilty as though there were no law on the subject. The law is wrong, and no man can have a right to avail himself of a wrong law to injure his fellow-beings; no, nor to benefit himself. Did the law even require a man to vend intoxicating drinks, he would have no right to obey that law, but would be bound to disobey it.

Go to the Bible, and you will learn from Daniel, from Shadrac, Meshac, and Abednego [[Dan. 3]], from Paul and Silas [[Acts 16:19]], Peter and John [[Acts 4:19; 5:29]], that God is to be obeyed rather than man. Invoke counsel of the souls of the martyrs whose spirits made their exit from gloomy cells through iron grates on the wings of an expiring breath to a martyr’s reward, and you shall learn from thence that no human authority can justify the least infraction of moral principle.

We ask the vender, then, “By what authority doest thou these things, and who gave thee this authority?” [Matt. 21:23] Do they say they have a license? This may be, but that license confers no moral right—it is just such a license as no one can have a right to give—a license to do wrong. It is a license to destroy men—a license to rob the innocent—a license to make widows and orphans—a license to convert the hunger of the drunkard’s family into plenty to put upon their own tables—a license to convert the rags of the drunkard’s half-clad children into silk and lace to put upon their wives and daughters—a license to convert the tears of the drunkard’s abused and neglected wife, into gold to put into their coffers or jingle in their pockets!

But will this license be an excuse in the day of retribution, when God shall make inquisition for blood? When the rum-seller shall stand at the bar of his Judge, and those whom he has destroyed shall stand around him; drunkards howling in his ears the reproaches of their own ruin, and their wives and children, loaded with all the fruit of his unholy traffic, pouring upon him the scalding, withering tale of their miseries; will he then look his Judge in the face and say, I had a license to do these things?

Let me say as I take my seat, that when the dreams of worldly interest shall have faded from the disordered imagination—when the lamp of life shall burn dim and hasten to expire amid the breaking in of light from the spirit world, and when eternity shall roll up its long concealed orb of abiding realities, and exhibit at one view the final and full results of this dreadful traffic, then will all wish there had been enacted and enforced a PROHIBITORY LAW!

[[Additional Biblical references are inserted here relating to the sermon.

“A sermon for the times: prohibitory laws” sermon by Rev. L. Lee in 1841, published by Wesleyan Book Room, New York, 1852.

Lee’s sermons were reprinted in 1975 “Five Sermons and a Tract, By Luther Lee, Edited with an introduction by Donald W. Dayton.” Available from Wesleyan Church Archives.]]